The horrors of the Nazi concentration camps during World War II remain a haunting chapter in history, with stories of unimaginable cruelty still emerging decades later. Among the 3,700 women who served as guards in these camps, only three faced justice for their roles in mass murder. One such figure is Charlotte S, a notorious female guard at Ravensbrück and Auschwitz, whose chilling actions—beating prisoners and unleashing her ferocious dog—left an indelible mark on survivors. As reported by the Daily Mail, Charlotte’s story is a stark reminder of the depths of human cruelty and the elusive nature of justice. How did someone so deeply complicit evade significant accountability, and what does her story reveal about the broader legacy of Nazi war crimes? Let’s delve into this dark history and uncover the truth behind Charlotte S.

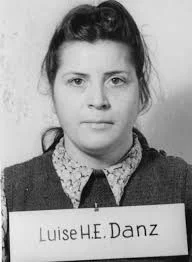

Portrait of female prison warden Charlotte S. Photo: Bild.

Charlotte S’s story is a disturbing glimpse into the machinery of the Nazi regime, where ordinary individuals became instruments of terror. As a female guard at Ravensbrück and later Auschwitz, she embodied the cruelty that defined these camps. With only three out of 3,700 female guards prosecuted for their roles in mass murder, Charlotte’s case raises questions about accountability, the role of women in Nazi atrocities, and the lasting impact on survivors. Let’s explore her actions, the context of her crimes, the justice she faced, and the broader implications of her story.

Charlotte S: The Face of Cruelty at Ravensbrück

Charlotte S served as a guard at Ravensbrück, a women’s concentration camp in northern Germany, where over 130,000 prisoners—mostly women and children—endured unimaginable suffering. Survivors describe her as a terrifying figure, her “gentle smile” masking a sadistic nature. According to a survivor’s account in the Daily Mail, Charlotte was “thin and had a ferocious dog always ready to bite prisoners.” She enforced brutal punishments, forcing prisoners to stand for hours in extreme weather—scorching heat or freezing cold. “If anyone moved, she would unleash the dog. Many couldn’t survive its bites,” the survivor recalled. These acts of violence, including beatings and allowing her dog to “devour” prisoners, cemented Charlotte’s reputation as a merciless enforcer of Nazi terror.

Her cruelty wasn’t limited to physical violence. The psychological torment of her unpredictable behavior—smiling one moment, unleashing horror the next—added to the prisoners’ suffering. Ravensbrück was notorious for medical experiments, forced labor, and mass executions, and Charlotte’s role as a guard made her complicit in these atrocities. Her actions reflect the broader role of female guards, or Aufseherinnen, who were integral to the camp’s operations, overseeing prisoners and enforcing the regime’s brutal policies. Posts on X echo the survivors’ horror, with one user stating, “Charlotte S’s story is chilling. How could someone hide such evil behind a smile?”

Of the 3,700 women who worked at Nazi concentration camps during World War II, only three faced justice.

From Ravensbrück to Auschwitz: A Trail of Terror

In 1943, Charlotte S transferred to Auschwitz, the epicenter of the Holocaust, where over 1.1 million people were murdered. Her tenure there was marked by a scandalous affair with an SS officer, highlighting the complex dynamics within the Nazi hierarchy. This relationship led to her pregnancy, prompting her to leave her role as a guard that same year. While her time at Auschwitz was shorter, the camp’s scale of horror—gas chambers, crematoria, and systematic extermination—meant even a brief stint implicated her in one of history’s greatest atrocities. Her involvement in both camps underscores the extent of her complicity, as she actively participated in the machinery of death at two of the most infamous sites of the Holocaust.

The role of female guards like Charlotte was critical to the Nazi system. Unlike male SS officers, who often held higher ranks, female guards directly managed prisoners, enforcing discipline through violence and fear. Their proximity to victims made their actions deeply personal, amplifying the trauma for survivors. Charlotte’s affair with an SS officer also sheds light on the blurred lines between personal and professional conduct in the camps, where power dynamics fueled both cruelty and corruption. An X user remarked, “Female guards like Charlotte S were just as brutal as the men. Their stories deserve more scrutiny.”

A Meager Reckoning: Justice After the War

After World War II, the pursuit of justice for Nazi war criminals was uneven, particularly for female guards. Of the 3,700 women who served in concentration camps, only three faced charges specifically for complicity in mass murder. Charlotte S was convicted of “mistreatment and theft,” receiving a mere 15-month sentence—a strikingly lenient punishment given the scale of her crimes. The Daily Mail notes that at 94, Charlotte still lives in Germany, refusing to discuss her past. This silence is emblematic of many former Nazi collaborators who evaded accountability, living out their lives without fully confronting their actions.

The leniency of Charlotte’s sentence reflects broader challenges in post-war justice. The Nuremberg Trials and subsequent proceedings focused primarily on high-ranking Nazi officials, leaving many lower-level perpetrators—like female guards—under-scrutinized. Limited evidence, survivor trauma, and the sheer scale of Nazi crimes made prosecuting every individual difficult. Charlotte’s case highlights a systemic failure to hold all perpetrators accountable, particularly women, whose roles were often downplayed as “lesser” compared to male SS officers. An X post captured the frustration: “15 months for such cruelty? Justice was barely served for Charlotte S and others like her.”

The Broader Legacy: Women in the Nazi Machine

Charlotte S’s story raises critical questions about the role of women in the Nazi regime and the complexities of accountability. Female guards were not passive bystanders; they were active participants, often as brutal as their male counterparts. Their recruitment—often young, working-class women drawn by stable jobs and authority—reveals how the Nazi system co-opted ordinary individuals into its genocidal machinery. Charlotte’s ability to blend back into society post-war, living to 94 without further reckoning, underscores the challenges of addressing complicity on a societal level.

Survivors’ testimonies, like those quoted in the Daily Mail, are vital to preserving the memory of these atrocities. They remind us of the human cost of the Holocaust and the need for continued vigilance against such horrors. The fact that only three female guards faced justice for mass murder highlights a gap in historical accountability, prompting debates about how societies confront their past. As one X user put it, “Stories like Charlotte S’s show why we must keep telling these histories—to ensure justice, even decades later.”

Charlotte S’s story is a haunting reminder of the cruelty that thrived in Nazi concentration camps and the incomplete pursuit of justice that followed. Her actions at Ravensbrück and Auschwitz—beating prisoners, unleashing her dog, and enforcing terror—mark her as a key figure in the Holocaust’s horrors, yet her 15-month sentence reflects a broader failure to hold all perpetrators accountable. As one of only three female guards prosecuted for mass murder among 3,700, Charlotte’s case underscores the complexities of confronting complicity. Her silence at 94 leaves unanswered questions, but survivors’ voices ensure her crimes are not forgotten. What do you think—how should history judge figures like Charlotte S, and how can we ensure justice for such atrocities?

Luise Danz’s story is a haunting coda to the Holocaust’s symphony of suffering—a tale of how evil thrives not just in the spotlight of monsters like Mengele, but in the dim corridors of administration. Her quiet killings remind us that genocide isn’t always loud; it’s often a form of paperwork, a suggestion slipped into a file, a whip crack in the frozen night. As fans of history, we owe it to the 15,000 souls she condemned—and the millions more—to remember her not as a villain in a vacuum, but as a warning. In an age of bureaucratic overreach and moral apathy, Danz asks: How many “quiet killers” walk among us today? Share your thoughts below—what does her legacy teach us about complicity? Let’s keep the conversation alive, so the silenced voices of Auschwitz echo on.

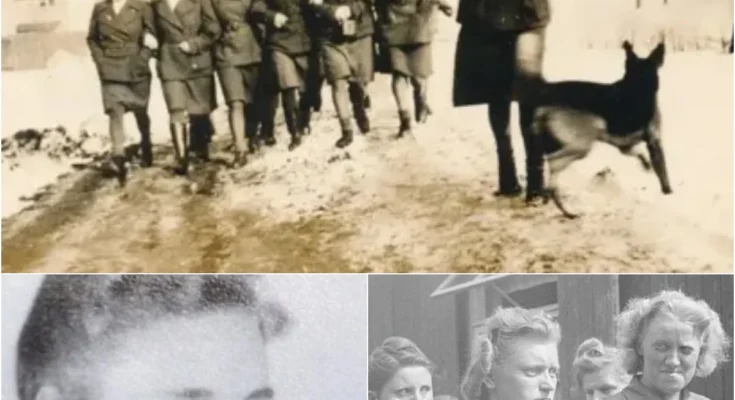

What set Danz apart from the more theatrical killers like Grese—who delighted in public whippings and shootings—or Mandel, who orchestrated medical experiments with a cold detachment—was her preference for subtlety. Eyewitness accounts from survivors paint a portrait of a woman who avoided the spotlight, yet her impact was devastating. Rather than dirty her hands with direct executions, Danz excelled in the art of the “recommendation.” As a senior overseer, she compiled meticulous reports on “undesirable” inmates—often women and children deemed too weak for labor—and forwarded them to camp commandants with suggestions for “special treatment.” In Nazi euphemism, that meant the gas chambers. Historians estimate her reports contributed to the deaths of at least 15,000 female prisoners, a number that emerged only after Allied forces liberated the camps and sifted through the Nazis’ own damning paperwork. It was a form of killing by proxy: clean, efficient, and deniable. “She was the ghost in the files,” one survivor later testified, “deciding fates without ever facing her victims.”

But Danz wasn’t entirely hands-off. When her bureaucratic facade cracked, her cruelty turned visceral and petty, a twisted outlet for the power she craved. Survivors recounted her fondness for the bullwhip made of cow sinew—a flexible, lacerating tool that left prisoners’ backs in bloody ribbons. She patrolled the barracks with it coiled at her side, striking out at the slightest infraction: a slow worker, a whispered conversation, or even a defiant glance. One particularly harrowing testimony came from a Polish Jewish woman who endured Danz’s “winter punishments” at Birkenau. In the subzero nights of 1944, with temperatures plunging to -10°C (-14°F), Danz would order non-compliant inmates to strip naked and lie in the snow for hours. “They froze like statues,” the witness recalled, “their bodies turning blue as she watched with a smile, sipping hot coffee.” These acts weren’t just sadism; they were psychological warfare, breaking spirits before bodies gave out. Unlike Grese’s flamboyant brutality, Danz’s was intimate, almost maternal in its deception—she’d feign concern before unleashing hell, making her betrayals cut deeper.

The war’s end in 1945 brought a reckoning, but not immediately. As Soviet and Allied troops stormed the camps, Danz slipped away, blending into the chaos of defeated Germany. It wasn’t until June 1, 1945, that British forces captured her in a routine sweep, her SS uniform traded for civilian rags. The evidence against her piled up like the ashes in Auschwitz’s crematoria: seized documents from the camps revealed her signature on death lists, corroborated by a chorus of survivor testimonies. At her trial in 1947 before a Polish court in Kraków—the same city where she’d once ruled as an overseer—Danz played the ultimate defense: obedience. “I only wrote what the commandant ordered,” she claimed, her voice steady as she shifted blame upward to the ghost of Heinrich Himmler and his chain of command. It was the Nuremberg defendants’ favorite alibi, but the judges saw through it. The prosecution laid bare her role in the systematic extermination of 15,000 women, linking her reports directly to gas chamber selections. On November 25, 1947, she was sentenced to life imprisonment, a verdict that echoed the gravity of her crimes.

Yet justice, in the fragile postwar world, proved fleeting. After nine years in a Polish prison, amid Cold War tensions and overcrowded cells, Danz was amnestied in 1956 and deported to West Germany. She vanished into obscurity, living quietly in Oldenburg as a seamstress, her past buried under layers of denial. For decades, she evaded further scrutiny, a footnote in Holocaust histories overshadowed by bigger names. But history has a way of exhuming the forgotten. In 1996, a dusty archive in Berlin yielded a bombshell: a long-lost SS file detailing Danz’s direct involvement in the murder of teenage prisoners at Mauthausen in September 1942. The document described how she had overseen the selection and gassing of adolescent boys and girls, deeming them “useless mouths” during a labor shortage. At 79, frail and wheelchair-bound, Danz was rearrested in a dramatic dawn raid. The trial in 1999 was a media circus, with survivors in their 70s and 80s taking the stand to relive nightmares. “She hasn’t changed,” one said, pointing at the stooped figure. “The eyes are still cold.” Convicted of accessory to murder, her age spared her a harsher sentence—three years in a minimum-security facility, where she served her time knitting and reading.

Freed by late 1999, Danz returned to her quiet life, but fate—or karma—had the final word. Just six months later, on May 15, 2000, she suffered a massive stroke and died at 82, alone in her apartment. No eulogies, no remorseful confessions; just a silent end to a life built on whispers of death.

Luise Danz’s descent into darkness began in her mid-20s, a time when many young women were dreaming of families or careers, but Danz chose the path of the Third Reich. At 26, in 1943, she joined the SS, the Nazi party’s elite paramilitary force, and was quickly thrust into the machinery of the Holocaust as an Aufseherin—a female overseer in the concentration camps. Her assignments read like a roadmap of hell: starting at Kraków-Plaszów in occupied Poland, where she monitored Jewish forced laborers under the brutal command of Amon Göth (the real-life inspiration for Schindler’s List). From there, she moved to the infamous Auschwitz complex, including its subcamp Birkenau, the epicenter of industrialized murder, and later to Mauthausen in Austria, a quarry camp notorious for its “Stairway of Death” that broke the bodies of countless prisoners.

In the annals of World War II’s darkest chapters, the Holocaust stands as a monument to human cruelty, where monsters walked among us in human form. While infamous figures like Irma Grese, the “Beautiful Beast,” and Maria Mandel, the “Queen of Auschwitz,” reveled in overt sadism, there was another whose terror was far more insidious—a silent architect of death who wielded her power not with screams or spectacles, but with the stroke of a pen. Meet Luise Danz: born on December 11, 1917, in a quiet corner of Germany, she would become one of the SS’s most elusive overseers, supervising horrors in camps like Kraków-Plaszów, Birkenau, Auschwitz, and Mauthausen. Unlike her flashy counterparts, Danz’s method was chillingly bureaucratic: reports that funneled thousands into gas chambers, all while she inflicted personal cruelties in the shadows. Her story isn’t just one of evil—it’s a stark reminder of how ordinary people can enable genocide through quiet complicity. As we delve into her life, prepare to confront a legacy that whispers louder than any shout.